Rowan is a Senior Lecturer in Agroforestry at the Faculty of Land and Food Resources, The University of Melbourne. With his family he is also the owner of the Bambra Agroforestry Farm in Victoria, Australia, where he practices what he preaches.

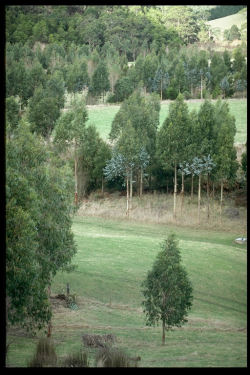

Bambra Agroforestry Farm is our private attempt at demonstrating how multipurpose forests can be integrated into a farming landscape. More than 40 commercial timber species have been incorporated into plantings for land degradation control, shelter, fire protection, shade, wildlife habitat and beautification. Since the first trees were planted in 1987, more than 4000 visitors from across Australia and overseas have taken our guided tour around the farm and witnessed demonstrations and debates about farm forestry.

|

|

| Left - The creek in 1987, unfenced, eroded and with willows spreading. Right - Six years later, trees for shelter, biodiversity, erosion control and possibly timber. (Photos courtesy of R. Reid) |

One of the most controversial plantings on the farm is the multipurpose buffer strip we planted along the eroded creek. We applied for, and received, government support for fencing and tree planting - although there was concern about my open ambition to incorporate non-indigenous (although native) species and manage them for high value timber. Electric fencing was used to allow the planting to follow the meandering creek, with the distance fenced out varying with the risk of bank erosion and rate of runoff. Pruned Eucalypts and Blackwoods now line the banks sheltering an understorey of native shrubs.

The aim was to produce quality timber within the constraints set by the needs of soil protection, enhanced water quality, wildlife habitat and landscape aesthetics. The species selected included local native understorey shrubs, regional selections of Blackwood (A. melanoxylon) for cabinet timber, and a number of eucalypts (primarily E. regnans, E. nitens and E. globulus) for sawlogs. Site preparation involved a careful spot application of herbicides - there was no soil disturbance or fertilizer application.

Over the subsequent years the better performing trees were pruned each winter using hand tools and ladders. All branches were removed from the bole of selected trees up to a stem diameter of about 8cm. I try to prune to a height of just over 6.5 metres to allow for a 6 metres saw log. Pruning enhances the quality of timber by eliminating knots from the mature wood. Poorly formed trees were thinned to waste leaving a forest of straight clean boles.

Sheep have been totally excluded from the riparian belt, except for some opportunistic summer grazing for fire and weed control, and the occasional rouges. The planted and naturally regenerating understorey is encouraged while any willows causing concern are controlled using the stem injection of herbicide. All debris from thinning and pruning are left to decompose on site.

|

Josquin Tibbits and Andrew Stewart inspect a 15 year old E. nitens growing along the creek that is 57cm in Diameter at Breast Height. (Photo courtesy of R. Reid) |

If timber production from a multipurpose planting like this is to be feasible the quality of each tree must to be high enough to ensure that it is viable to harvest and market in small lots. With this in mind our aim was always to produce high-pruned sawlogs of about 60cm in diameter. Tree diameter growth has been regularly monitored. Although the better performing Eucalypts had reached diameters of over 40cm at 1.3 metres above the ground (breast height) by age 10 years, annual growth data suggested that diameter increments were declining due to increasing competition.

The forest clearly needed thinning if the target tree size was to be achieved within 20 years. Rather than thin to waste again, we chose to undertake our first experimental harvest and sawing trial of Shining Gum in 1998 in cooperation with CSIRO (Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). A small number of 10 year old logs were milled, the timber dried and some furniture produced. The trial proved to my satisfaction that I was on the right track: young eucalypts can yield high quality timber if well-managed but achieving a large diameter is critical. I needed to reduce competition to maintain diameter growth - so I kept thinning.

I now aim for a spacing of no less than 6m between any two eucalypts trees and a final stocking of less than 120 trees per hectare. Rather than start with 3 metre spacings, I plant groups of 2 or 3 trees at 6 metre centres. The best of the group is selected at the first pruning and the others culled. This gives a stocking of around 280 trees per hectare, none of which are within 6 meters of each other. Further thinning reduces the stocking down to around 120 high pruned trees per hectare.

Eucalypts certainly respond to being given space. Above the pruned stem the canopy fills out providing the leaf area required to drive diameter growth. At age 17 years, my best trees have a canopy diameter of around 10 metres and are over 60cm in trunk diameter at breast height. The space between the trees is available for understorey shrubs or pasture.

|

Manual harvesting can be viable if the trees are valuable, Josquin Tibbits, faller. (Photo courtesy of R. Reid) |

Last year, we undertook a larger sawing trial. A semi-trailer load of pruned log was harvested using a well-trained chainsaw operator and my farm loader. The average breast height diameter of the 16 year old trees was 50cm. In most cases, harvesting simply required dropping of the electric wires from the fence posts and hand falling out into the adjacent cleared paddock although about a third of the trees were felled into the creek itself. That's right we felled some of the trees into the creek. Scientists now believe that our creeks and rivers are suffering from a lack of woody debris. Whilst most conservation projects provide very little dead wood, our creek is now well endowed with broken limbs, trunks and leaf litter that create pools and enhance wildlife habitat. Because I am only interested in harvesting the 6m butt log, I am leaving more than 15 metres of trunk in the ecological system. The tops of those trees harvested out into the paddock had to be cleaned up and were later sold for firewood - a cost neutral option at best.

|

A load of pruned logs harvested from the creek leaves the farm in 2004. (Photo by courtesy of R. Reid) |

The logs were milled by Black Forest Timbers along with some 65 year old Shining Gum logs of similar diameters from native forest. The timber has been kiln dried and we are now assessing timber quality. The native logs were certainly very clean yielding a high proportion of furniture, flooring and joinery grade timber. My 16 year old logs produced some beautiful timber although the logs were still not large enough to produce the wide boards that attract the highest prices. Interestingly, fiddleback was quite common in my timber and something we will be looking into more. I have many hours of data analysis in front of me.

For now, I've got six cubic metres of dried sawn timber back on the farm. I'll be using some for studies of wood quality and making furniture myself. Some will be sold to people who prefer to use farm-grown native hardwoods over imported or native forest timber. Not only can they be assured the timber they are buying has not been harvested from a native forest, they can take pride in the fact that their purchase has actually enhanced biodiversity and improved water quality.

I continue to prune and thin my trees with the aim of growing large clean butt logs. I'm now aiming for trees of over 70cm in diameter at breast height. Each tree would yield around 2 cubic metres of saw log (6 metre long log) from which I could extract around 1 cubic metre of sawn timber, half of which would be of the highest grade and value. Between the trees I have a healthy understorey and have already begun planting rainforest timbers like Silky Oak (Grevillea robusta) and Myrtle Beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii), and specialty timbers like River Sheoak (Casuarina cunninghamiana).

In the larger gaps, where there is sufficient light for young eucalypts, I replant with a range of species to hedge my bets. Shining Gum is certainly a fast grower but is susceptible to wood borers and root rot. Other eucalypts species I like for sawlogs are Sydney Blue Gum (E. saligna), Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata) and Yellow Stringybark (E. meulleriana).

Harvesting sawlogs from farm plantings has added an additional dimension to our property making it more attractive, challenging, and I hope, more valuable. Most visitors agree that we have increased the farm's capital value and ensured that future generations will not have to wait a full rotation in order to enjoy the benefits of owning a productive forest. I have also had the satisfaction of growing, harvesting, milling and drying my own timber, and making furniture from it. Something most professional forest scientists never experience.

It is possible to marry tree growing for conservation and profit. Unfortunately, most agencies and industry groups promote either one or the other and actively discourage farmers from integrating production, biodiversity, soil conservation and aesthetics. I know that if my farm was in another state, I would not be allowed to harvest logs from the creek! Such laws just encourage us to continue grazing stock in waterways, exacerbating erosion and nutrient problems.

Most farmers see the logic of multipurpose forestry. They know that conventional large monoculture plantations just compete with agriculture for the best land and are, in themselves, extremely risky investments. By planting trees along waterways, fence lines and on less productive parts of the farm, agricultural productivity can be enhanced along with the sustainability and attractiveness of the farm. If these same trees are managed for timber then this can be a bonus, icing on the cake.

By Rowan Reid, (Rowan.Reid [at] unimelb.edu.au) with Russell Washusen of CSIRO, Josquin Tibbets (Faller) and Black Forest Timbers.