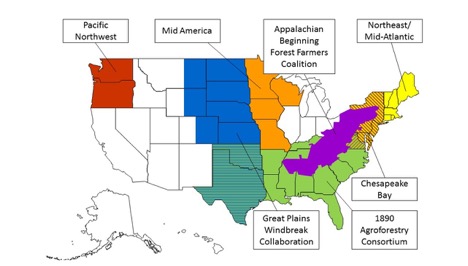

AFTA represents temperate North America, an area of diverse ecological, political, and agricultural characteristics. Many regions are associated with agroforestry working groups, communities, and networks that have a long history (Figure 1). Some of these groups were highlighted in the National Agroforestry Center’s “25 Years” issue of Inside Agroforestry. These regional working groups have helped amplify awareness and establishment of agroforestry systems by providing regional expertise and networks for agroforestry education, outreach, research, and policy (Figure 2).

One of the strengths of working at a regional scale is the ability to take different approaches. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to collaboration and networking any more than there is a one-size-fits-all approach to agroforestry systems for producers. Each of the groups works in response to regional ecosystems, agriculture, economies, and communities. Participants have also varied from group to group, with some including producers and practitioners, others focused on researchers, some involving technical assistance providers, and, most often, a collaboration of all of the above.

Figure 1: States and regions represented by a selection of the agroforestry working groups and networks in the United States.

However, forming a working group is not the same as maintaining one. Many working groups are initially formed to implement a grant or project. Once the project is complete, what is their role? How can they determine and achieve their goals? Do they operate as networks? How are they funded? What are the paths to engagement for new members?

Looking across North America, working groups are addressing these questions in different ways. Some form sub groups and sub committees to carry out specific tasks. Others disband when a project is over. Some persist solely to foster communication. Still others are not as active as they would like to be. Potential roles for working groups may include examining the conservation, economic, or community needs that agroforestry can help meet, identifying the types of support needed for agroforestry to expand in their region, or reflecting on agroforestry’s role in broader efforts in agriculture, forestry, conservation, and food systems. Working groups may also address questions such as how do we better support those interested in agroforestry in an inclusive way, are there gaps in the regional network and how do we analyze them, and what does the work look like day-to-day or on a monthly basis when everyone involved already seems to be busy?

Figure 2: Many agroforestry working groups provide agroforestry training and workshops. This training was held in 2015 in Pine Lake, Minnesota.

If you are interested in thinking more about how working groups, communities, and networks can more effectively support agroforestry, please join us for the panel “Looking ahead: what is a regional agroforestry working group?” at the North American Agroforestry Conference in Blacksburg, Virginia June 27-29, 2017. You will hear from representatives of the Pacific Northwest Agroforestry Working Group, the Northeast/Mid-Atlantic Agroforestry Working Group, the Mid-America Agroforestry Working Group, and the North Carolina Silvopasture Group, and we would welcome your perspective as well. If you are unable to attend the North American Agroforestry Conference, I’d still love to hear your thoughts on this important topic as we work together to foster collaboration and agroforestry implementation.